How Russian Natural Gas Exports to Europe Have Changed Since the War

Since fighting broke out in Ukraine nearly seven months ago, Russia and Europe have been waging an economic war over energy, one that could have dire consequences for millions of households and businesses across the continent.

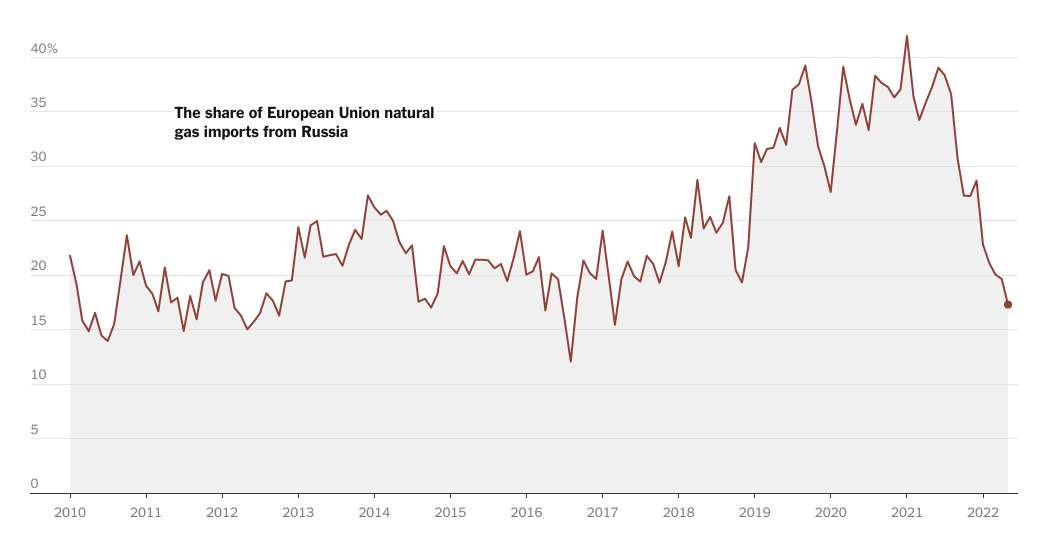

Last year, nearly 40 percent of the natural gas used to heat homes and power businesses throughout the European Union came from Russia, one of the continent’s largest and most important trading partners for energy.

Now barely half that amount enters Europe, government statistics show, stoking fears of shortages this winter.

As part of a wide-ranging effort to cripple Russia’s economy, which is largely propelled by the sale of fossil fuels, the European Union has imposed huge sanctions and has vowed to eventually stop buying Russian gas.

But with Europe still dependent on Russia in the meantime, Russia has retaliated by severely restricting the flow of energy to Europe, forcing governments to try to find alternatives.

President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia “is using energy as a weapon by cutting supply and manipulating our energy markets,” Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, wrote on Twitter.

This battle has proved costly for both sides.

Alternative buyers of Russia’s oil and gas, including China and India, are taking advantage of the situation and pushing for steep discounts. That is limiting the revenue that Moscow needs to power its economy, as well as to build pipelines and ports to supply energy to Asia more regularly.

Even countries that don’t import Russian gas are suffering, because electricity prices are closely linked to gas. The benchmark wholesale price of natural gas in Europe, which has been incredibly volatile since the war in Ukraine began, is roughly four times what it was a year ago.

The average European household is facing a monthly energy bill of 500 euros ($494) next year, triple the amount in 2021, according to estimates by analysts at Goldman Sachs. Applied to all energy users, that implies a €2 trillion increase in spending on heat and electricity.

The squeeze is particularly acute in Germany, Europe’s largest economy, which relies on Russia as its biggest supplier of gas. The bulk of it flows through Nord Stream 1, a 760-mile passageway that connects the two countries via the Baltic Sea.

Since the war, the Russian-controlled operator of the pipeline, Gazprom, has twice reduced the amount of gas it sends to Germany and twice shut the pipeline down for maintenance. After the most recent shutdown last week, Gazprom postponed a planned restart, citing faulty equipment, and provided no timeline for reopening, with officials in the Kremlin blaming sanctions for delaying repairs.

Critics suggested that last week’s move was a cynical response by Russia after finance ministers for the Group of 7 countries said they had agreed to impose a price cap mechanism on Russian oil in a bid to choke off some of the revenue Moscow still generates from Europe.

The indefinite shutdown nonetheless raised fears that it could become permanent. A complete cutoff from Russian gas would push Europeans’ energy bills even higher and hit the region’s economy even harder, with experts projecting a potentially deep recession in the most exposed countries. A shutdown would subtract nearly 3 percent from Germany’s economy next year, economists at the International Monetary Fund have estimated.

“In our view, the market continues to underestimate the depth, the breadth and the structural repercussions of the crisis,” the Goldman Sachs analysts wrote. “We believe these will be even deeper than the 1970s oil crisis.”